Hi everyone.

The last few months have been a blur of not updating my website or this blog, as I tried to (a) get The Duchess War ready and (b) get my kitchen to the point where it had dry wall, running water, and a refrigerator. To my great relief, (b) has now been achieved. I’m still working on (a). To give you some idea when The Duchess War is coming, I just sent the book to the copy editor. I’m going to be running proofreading in parallel. As soon as I get everything back from the people who have it, I will hit “publish”–but that is unlikely to happen before Thanksgiving, unfortunately. I am hoping it will not take a great deal of time after Thanksgiving. As soon as I have a more precise ETA, I will let you all know.

So, to answer some questions.

Courtney, whose fault is it that the book is taking so long?

Mine. Completely mine. Everyone who has been working with me has been absolutely stellar about turning things around with high quality on short turnarounds and with me telling them they’d have the book on one day, and then not having it done for two weeks after that.

Why did you do that?

Because I am really bad at estimating how long it’s going to take me to write a book. The best way I can think of to explain this goes like this: I’m delusional.

No, really. I am.

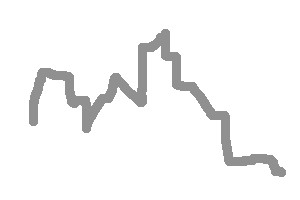

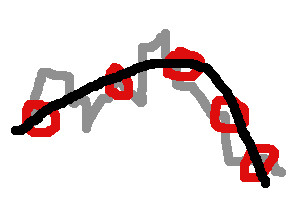

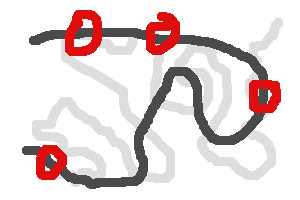

When I’m writing a book (and not all authors do things like I do, luckily for them), what usually happens is I write the first draft and it looks something like this.

There’s a lot of stuff in there that goes in directions that aren’t useful, and things that are left out that should really be filled in. Some things don’t make sense, or aren’t emotionally accessible, or aren’t dorky enough for my tastes.

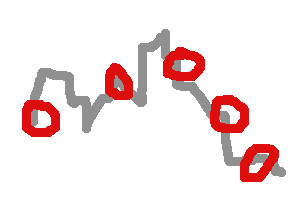

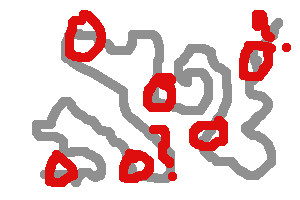

So I go back over the manuscript and try and figure out the parts that I’ve written that are actually good, the parts I’ve written that are okay but need work, and the parts that are utter crap. I usually end up at this point identifying what the story is.  Those are the red dots in the picture to your right: the elements of the story that drive it from place to place.

Those are the red dots in the picture to your right: the elements of the story that drive it from place to place.

That sounds weird, because how is it that I can write a story without knowing what it is? Answer: I don’t know, but I do it all the time. Every book I write, I usually have some idea what I think the story is, and then I end up jiggling it and reworking it and I end up with a beast that is slightly different.

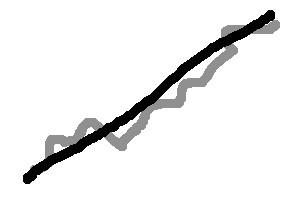

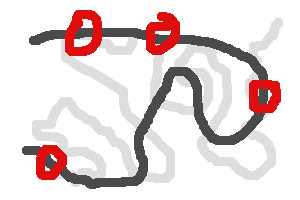

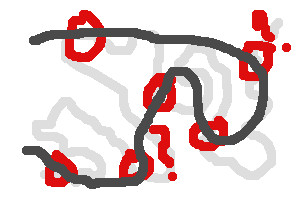

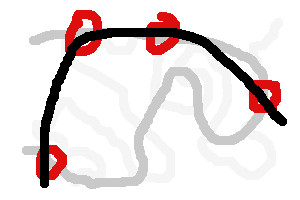

Once I’ve figured out what the story is, I can usually do a pretty good job of going back through and smoothing out the arc of the story.

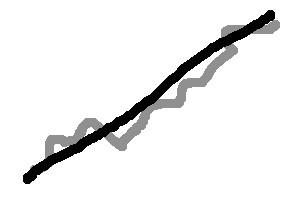

If I’m doing my job, we end up with something like the black line to the left. (For those of you who want to criticize the black line for not following proper story structure, consider this for illustrative purposes only.)

If I’m doing my job, we end up with something like the black line to the left. (For those of you who want to criticize the black line for not following proper story structure, consider this for illustrative purposes only.)

That’s the basic way I write a book. In reality, it’s more confusing than that. I write books out of order–I have some scenes I think are going to happen, so I write those, and those make it clear that there are other scenes I have to write, and those make it clear that there are other scenes I have to write… So in reality, just getting that first gray line down can sometimes be a challenge.

(Incidentally: I do not advise that anyone write the way that I do if you can possibly help it. I am profligately wasteful with my words! Sometimes I talk to other authors, and they say things like, “Oh, I just deleted 1,200 words, and it hurt…but I saved them in a file and I know I’ll use them again later!” Those people make me feel like I’m the world’s biggest word waster. Sometimes, I cut 10,000 words at a drop, and I never end up using them. They suck. I don’t see how I could use them. That’s why I cut them. I wish I didn’t write words that sucked in the first place, too.)

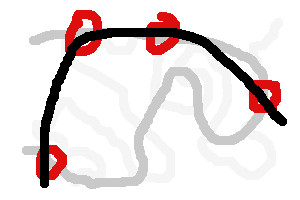

In any event, here’s why I’m bad at figuring out when things are going to get done. Every once in a while, I get a book that is a gift. I write a first draft, and it is like this:

I look at it; the smooth arc of the story is already in place, and I revise it, and ends up like this.

Those books are gifts. They are gifts from the writing gods. Unveiled, for instance, took me three and a half months to write, while working a fairly hefty day job. It was the easiest book I’ve ever written.

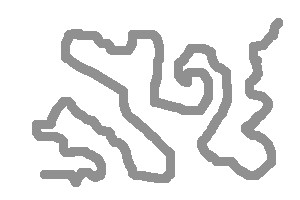

Then there are books where the first draft is like this.

The motivations are murky. The plot is byzantine. I write scene after scene which seem to be moving the book only in the direction of fiery doom. I go through the pages, scratching my head. It looks like there are some good points in what I have? Maybe these ones?

So I get out my trusty pen and try and connect those dots.

The result, alas, is still unsatisfying. So I iterate the process: look at what I have, try and figure out what’s important. This time around, different things stand out.

Finally, I’m able to come up with something that makes sense, something that is actually a story.

Needless to say, when you have this kind of a book, it takes much, much longer.

What it really feels like is this: Imagine that you’re exploring a territory, and you’re trying to estimate how long it is going to take you to get to Denver. You don’t have a map. You’ve never been through this area. You’ve never talked to anyone who has been where you are, and there is no civilization, anywhere, so you’re totally on your own. But you do have a GPS system, and you know the coordinates for where Denver is.

If you’re lucky, you’re in Kansas City, and you can walk in a straight line directly to Denver, as the crow flies. If you are mildly unlucky, you’ll be in San Francisco, and you’ll have to find mountain passes, or go way out of your way. That will take a little exploration, and if you estimate your time as the crow flies, you’re probably going to be off by a good margin.

If you are extremely unlucky, you’re in Antarctica, and you’re going to have to discover modern nautical equipment first.

My problem as a writer is that when I estimate completion times, I assume that every book is a gift book. I’m always extremely optimistic. I give time estimates as the crow flies, while blithely ignoring the fact that the crow isn’t flying. She’s trying to figure out how to build a boat out of nothing but ice and extremely angry penguins.

I do this all the time, and I never learn my lesson, and it’s very hard for me to stop because honestly, if I sat down and told myself, “Courtney, you are going to struggle with writing this book for the next eight months, and everything you put on paper in July, you will eventually delete in a fit of rage,” I would just give up. My ridiculously optimistic delusion is the only thing that keeps me going, so I stick to it doggedly. I say stupid things like, “I have written 80,000 words, and a book is 90,000 words! Therefore I am almost done!” — ignoring, of course, that 40,000 of those words are crap and will melt away. I say things like, “If I only wrote 9,000 words a day for the next week, I will have this done by Saturday!” — ignoring, of course, that I have only written 9,000 words in a day twice in my life, ever, and if I had 9,000 words a day slipping off my fingers, I would be done already.

I can say all this now, and I can laugh at myself because I’m no longer dependent on penguins to save me, so it’s all good. But I will forget that this happens as soon as I’m working on another book.

In any event, I’m sorry I’m so bad at estimating when books are going to be done. I can’t even promise not to be delusional in the future. But I will try not to share my delusions with you from here on out.

But:Â The Duchess War shouldn’t be much longer. At this point, Denver is in sight, so I might know what I’m talking about.

If you want to get some inkling about the convoluted evolution of this book: In the very first scene which I envisioned for this book, way back when it was a tiny little germ of an idea, the hero went to a ball with the intent of releasing 500 live mice on the dance floor.

Read the book when it comes out. Then come back and scratch your head trying to figure that one out.