There’s a debate ranging about pricing. I’m not trying to take sides between the parties that have been on opposite sides for the last week (Macmillan/Amazon). For the record: I am 50% less likely to buy a St. Martin’s press book, because they are pricing their e-books of mass market releases at $14, than I am to buy books from any other house. If I bother to get a St. Martins book in print, I will read it. Otherwise, sorry, too bad. Macmillan, a $14 price on a mass market release is stupid. You should never charge more for the e-book than for the print book. And you should seriously consider making the e-book more valuable to readers by allowing for limited sharing capabilities and removing DRM.

Also for the record: Nothing that I say in this post about a price point higher than $9.99 is applicable to what I think of as general-interest fiction: mainstream romance, science fiction, probably even vast swathes of literary fiction, non-fiction like biographies of famous stars… you get the drift.

Also also for the record: It’s obvious hyperbole to say publishing can’t survive at a $9.99 price point. Harlequin Enterprises (my publisher) has been very profitable in these down times. In a given month, they release hundreds of books. One or two of those–maybe–will be a hardcover or a trade paperback. So threats that publishing will disappear if prices are lowered are to my mind demonstrably, provably wrong. Publishing will survive. It is obviously possible to make a price point much lower than $9.99 profitable, and to run a publishing company on that basis.

But this is not to say that publishing won’t change as a result of a $9.99 price, and while some of those changes would be welcome, some of them sound pretty awful to me. In order for a publisher to decide to print a book, they create a profit/loss sheet. I have never seen one. I don’t know what it looks like. I have no idea what goes into it. But in limited form, it goes something like this:

Expected fixed costs: Editing: $W. Cover: $X. Copy-editing: $Y. Author’s advance: $Z. Marketing: $0 (ha ha, just a little joke, I’m kidding)

Expected variable costs: Printing: $A. Shipping: $B. Author royalties (once the author has earned out). (and so forth)

Expected gross income=(# of copies sold) * price * percentage that publisher takes.

The “expected gross income” will vary substantially from book to book. The publisher understands that increasing price decreases number of copies sold. The publisher (ideally) wants to set the price such that it maximizes the expected profit. If there is no price where the publisher can make a profit, the publisher will choose not to publish the book. (Incidentally, the author is making a similar calculus: she’s adding up profits and losses and figuring out if it’s worth her time to write a book. Some of the author’s profits will not be strictly monetary, but that shouldn’t stop you.)

Now, as I said earlier, I firmly believe that anything written for a general-purpose audience is such that the expected profit will be maximized at or below a price of $9.99. This is because I think general-purpose audiences read primarily for entertainment and enjoyment. When you price things within their budget, they will choose to read more; if you price things out of their budget, they’ll choose to either read other things, priced at $9.99, or will engage in some of reading’s economic substitutes, like seeing movies or going miniature golfing. Most general fiction, and certain kinds of non-fiction, have somewhat elastic demand curves: lowering price easily increases demand, and so when you’re looking at your “expected income” line above, twiggling the price down a bit gives you a corresponding twiggle up in the number of sales. You can see this effect in action:Â paperback versions of most books sell way more copies than the hardcovers of the same book

But there are some books where demand is not so elastic in response to price. Take, for instance, this book: The Parkinson’s Disease Treatment Book: Partnering with Your Doctor to Get the Most from Your Medications. This is not something that I would go out and purchase, ever, whether it was priced at $9.99, $49.99, or $1.99. If I had Parkinson’s Disease, or a loved one had Parkinson’s Disease, my guess is I would not say “screw this book and its $37.95 price! I am going to go play miniature golf instead.” The number of copies the publisher can expect to sell of this book is probably small, relative to, say, Palin’s Going Rogue. If the maximum price they can choose to put on it is $9.99, do you think they’re going to publish it? My guess is no.

And even if you think that publisher would make money on that particular book about Parkinson’s above, are you sure you can say the same for books like Living with Haemophilia or Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Guide for Patients and Families?

The people who need these books really need them, and the people who don’t won’t buy them at any price. Publishers will only publish books that they believe (however rightly or wrongly) will make money. Authors will want to get some minimum compensation for their time–and will at least hope that their advance covers their fixed costs. If there is a book that holds a tremendous appeal for a small demographic, a set $9.99 price tag might not cover costs (either author costs or publisher costs). Books that are needed (or wanted) by a small segment of the population will cease to be profitable, and a $9.99 price tag means we’ll stop seeing some of these books altogether.

Likewise, there are some kinds of fiction that do not usually appeal to the general population. The audience for these books is small, but their demand is insatiable. They would rather pay $14.99, or $19.99, or even $29.99 for these books, than not have them appear at all. The general population usually won’t pick up these books for any number of reasons. Today, these books get published because publishers can charge $29.99 for them and recoup the editing investment–hoping that the small group of insatiable fans of these sorts of work will buy enough copies to make their money back. In a world where books cost $9.99, I’m not sure that will be true.

And maybe you’re thinking–well, so what, Courtney? If most people don’t want to buy those books, why should we care about them?

Well. That’s because those are going to be books written overwhelmingly by minorities: gays and lesbians, african americans, latinos and latinas, certain religious groups. Walk through the African American Studies section sometime, and count how many mass market paperbacks there are–and then compare that to the number of mass market paperbacks there are in the general “romance” or “mystery” sections. Count the number of hardcovers and trade paperbacks. (It’s the hardcover releases that are the true bellwether here: if a book has a planned release that is hardcover only, it is because the publisher doesn’t think a trade/mass market release will be profitable.)

It breaks my heart that books written by and about black people (and by and about other minority groups) are not usually purchased by the general population. But it’s true. And so when people start saying that categorically, no books should ever cost more than $9.99, and state with certainty that all purchases would increase if the price point were just low enough, to the point where it would make up the difference in sales… I just have to wonder if those people are considering the sort of books where you aren’t going to get those extra numbers, anywhere, no matter where you set the price.

A $9.99 price wouldn’t kill publishing. But it would change it. In some ways–in many ways–it would be a good thing. But I think that a hard price ceiling would kill diversity in publishing. It would mean that the only market rational business people could go after was a general purpose market. And I think that would leave us, as a society, impoverished.

I’m not saying that Macmillan is right–far from it. I’m not saying that Amazon is wrong–far from it. I am saying that we need to avoid categorical statements. Some books really do need to be priced over $9.99, or it simply won’t be profitable to produce them. And if we drive those books out, publishing will adapt by not selling them.

(Before you say the solution is then to self-publish, do keep in mind that the author is making the same calculus as the publisher. This is especially true for nonfiction. If the maximum price is one where it’s not worth the author’s time and effort, there is no point publishing whether as a self-publisher or otherwise. Self-publishing may be the answer for some of this, but it’s not the answer for many of these books. If we relied on self-publishing, I suspect that investigative nonfiction would disappear–nobody is going to spend 8 years figuring things out if they can’t get compensation. Self-help books based on useful facts and studies will disappear, for a similar reason. But even authors of fiction written for small demographics will find themselves writing fewer books, as they have to work more to compensate for the reduced income. Self-publishing might save some of the books that would otherwise get priced out of the market, but it won’t save all of them.)

Before I end, I want to repeat what I said at the beginning: This isn’t about Macmillan/Amazon. My goal is not to defend either Macmillan’s or Amazon’s current pricing practices. I have no financial dog in this race: my books (in North America[1]) are already priced below $9.99, and my publisher already prices the e-book version of my book below the print version of the book. I do not imagine a future when a book I write will be released in hardcover. But I do think that it’s naive to think that all hardcover releases are like Stephen King hardcover releases: books set at a price point designed to gouge the public into price discrimination. Some of them are priced at that point because it is the only profitable price at which that book can be produced, and removing the price point means the book won’t be published.

——

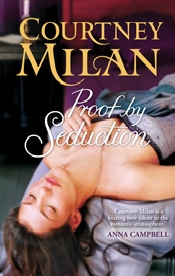

[1] A footnote: I started thinking about this question because I discovered my debut novel will be out from Mira in Australia/New Zealand in March of this year. Which is great! And they’ve featured the Anna Campbell quote, which is doubly great. The price tag, however, absolutely shocked me. A friend of mine from Down Under assured me that this was normal: the market there is 7% of the size of the North American market, and so the fixed costs for the books get averaged out over fewer books, resulting in what looks to my US-trained eye like fairly hefty prices. I’m very curious to see how AU/NZ pricing will hold up under increased pressure from global bookstores.