The words “historical accuracy†do not mean the same things to all people. This is, in large part, because readers read historical fiction for different reasons.

More after the jump.

The words “historical accuracy†do not mean the same things to all people. This is, in large part, because readers read historical fiction for different reasons.

More after the jump.

To the extent that I have a reputation in the online community of authors and readers, I’ve staked it on trying to speak clearly, intelligently, and correctly about things that I know about. I may not always succeed, but I always make the effort.

This is particularly true when it comes to legal matters. That’s why I post about the First Amendment, the Google Book Settlement, and the legality of text to speech on Amazon’s Kindle. It’s also why I post about annulment and debtor’s prison. Even if I think I know something cold, I don’t post anything legal without checking and double-checking the law first–even if I am posting a one-off comment on Dear Author.

While people may not always agree with my legal analysis, I want them to trust that I can back up what I say with solid, intelligent arguments. I want you to be able to trust that when I comment on Dear Author historical first pages saying, “this is legally possible” or “this is legally not possible,” that I’ve thought it out and looked it up and can provide pages of citation, if necessary. In fact, I will often provide them before I’m asked.

I don’t say anything about legalities without checking that I am right, and for good reason. My reputation on this question really, really matters to me–both because of what I say online, and because I write books that sometimes have legally intricate subplots.

At its heart, Unveiled, my upcoming February release, is about the interaction between two families: the Dalrymples, the children of the current Duke of Parford. They were declared bastards when the marriage that produced them was found to be bigamous. Then there’s the Turners, distant cousins who stand to inherit when the duke dies.

The Dalrymples aren’t taking this lying down, though: they’ve asked Parliament to legitimize them and restore their inheritance. This pending bill is a big part of what pits Ash Turner, my hero, against Margaret Dalrymple, the heroine.

I’ll stake my reputation as an author on the validity of that legal arrangement: the bastardization, and the ability of Parliament to legitimize bastards and restore their inheritance.

The correct statement of the law on legitimized bastards is this:

Where a person is admittedly a bastard by birth, there is no way, generally speaking, in which he can be made legitimate, except by Act of Parliament.

That exception–that you can become legitimate and inherit by Act of Parliament–is what Unveiled depends on. The disinherited Dalrymples are not seeking legitimation through ecclesiastical decree. They’re not relying on some technicality in canon law. They’re going directly to Parliament and saying, “We will not be able to inherit unless you pass a law that says we can.”

I know Parliament can do this for two reasons. First, and most generally, the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty says that Parliament can make or unmake any law it wishes. The only thing it can’t do is bind future Parliaments. So if there’s a law that says that bastards can’t inherit, Parliament can undo that law.

Second, we know that this can happen specifically because bastard children have in fact inherited by Act of Parliament. For instance, Parliament legitimized the children of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancester, allowing them to inherit from their father everything except the possibility of succession to the throne. Parliament also legitimized the children of Sir Ralph Sadler, whose wife was a bigamist (she believed her first husband was dead), and stated that their children “shall att all tymes hereafter for ever be had, reputed, taken, esteemed and adjudged legitimate and lawful children begotten of the body of ye said Ralph Sadler, and shall be inheritable as well to the same Ralph Sadler…to all intents, constructions, and purposes, as they hadde been ingendered, begotten, and borne, in lawful, perfect, and indissolvable matrimony.” You can read the entire text of that Act here.

I modeled the putative Act of Legitimation in Unveiled after the real-life Act passed for the benefit of Ralph Sadler’s children.

For a more comprehensive discussion, footnote (g) on this page of The Laws of England collects cases of legitimation by Act of Parliament, including a discussion on the particularities of inheriting through such legitimation.

So if you are wondering, for any reason, whether the arrangement in Unveiled is valid…it is. I research these things very thoroughly. If you ever have questions about the validity of any of the legalities I mention in my book, please e-mail me and I will be delighted to share with you the reams of research on the subject. And, lesson learned: next time, include an author’s note. Just in case.

I’m not allowing comments to this entry, not because I want to squelch discussion, but because I don’t want to tempt myself to say any more than I have.

That tells you that this is a more passive-aggressive post than it really should be–and I wouldn’t have said any of this if I didn’t think that this reflected not only on Unveiled itself, but on the character and reputation that I have painstakingly tried to establish.

I am in a happy place, because I finished a book! This is exciting, and so I’m going to talk about something even more exciting: impotence. This is because it has come up on at least four occasions within the last day–most recently, in this blog on All About Romance’s site, where Jane Granville makes the comment that “all of us can think of at least one book where the heroine got an annulment based on non-consummation (whether this is legally legitimate is up for debate).”

I suppose the question of annulment for non-consummation is up for debate, in the same way that the question of whether cats are reptiles is up for debate: you can have lengthy discussions about things that are questions of fact, and people can, in fact, disagree. But this isn’t a disagreement about whether vanilla ice cream is better than chocolate ice cream. It’s a disagreement where one person is right, and the other is wrong.

So, let’s settle this debate once and for all.

Nonconsummation, in and of itself, was never grounds for annulment. It was, however, a necessary (but not sufficient) component of seeking an annulment on grounds of impotence. And, here’s the kicker–today, when we think of “impotence,” we tend to think of it as a strictly medical condition that deals with the question of whether the man is capable of getting it up and using it, but what was meant by impotence back then doesn’t track modern meaning. A few things to consider:

So how does this play out? If you want to get an annulment on grounds of impotence, you are going to have to prove that you are impotent. You can do this a couple of ways. First, you can submit to medical evaluation. But remember that you can claim that are impotent with respect to a particular spouse–how on earth would you prove that to a doctor?

Well, this is where nonconsummation finally becomes an interesting question. Up until this point, nonconsummation would have been proof that the parties in question were not impotent. But the rule was that if the medical evidence was inconclusive, the courts would require the spouses to cohabit for three years. If they were able to do so without consummating the marriage, the court would presume that the couple was incapable of having sex, and they would annul it.

So nonconsummation, in and of itself, can be a grounds for annulling a marriage. But it has to be nonconsummation for three years of cohabitation–something that no romance couple has ever managed to accomplish.

The clearly readable A Handbook of Husband and Wife lays all this out, including a discussion on how these rules would vary in Scotland. For those who might get annoyed that this is technically a book about Scottish law (even though the author talks about England and Scotland), the same rule is discussed (in less clear terms) in A Practical Treatise on the Law of Marriage and Divorce, which is all about England.

So you want a marriage to be annulled for impotence? You need to live together for three years. And not just be married for three years, but generally live in the same place.

You may have heard that ICE (that’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement) has seized several domains that it believes are related to piracy. I’m not sure why ICE is doing the seizure, as compared to, say, the DOJ or DHS. I have conspiracy theories I can spin about border exceptions, but they’re kinda paranoid, and I want to reserve my paranoia for twitter, where I’m stuck with 140 characters.

(Okay, fine. I’ll be paranoid on my blog: one possibility why ICE is involved is that the people who ran these domain names are outside the US. The theory would be that we can then seize their stuff without due process–yay border/noncitizen exceptions! This is so paranoid on my part that I’m almost ashamed to write it. I don’t want to believe my government just claimed that it had a right to censor any internet site outside the United States, and that noncitizens don’t have a right to bitch about it. I so want my paranoia on this to be just paranoia, because otherwise we are so far into 1984 territory that I want to vomit.)

In any event, needless to say, I hate this. I don’t understand how this is not the very definition of a prior restraint–that is, blocking someone from speaking and then subsequently requiring them to prove that their speech is okay. Free speech 101: This is prima facie intolerable. This wasn’t even thinkable in 1792. How are we thinking it today?

This isn’t how we swing here in the United States. We believe in being innocent before being proven guilty. If these guys are copyright infringers, by all means prosecute them in federal court and seize the domain names upon conviction. But I just cannot possibly fathom a world in which someone thinks it is okay for the federal government to shut down a website and literally block free speech without first obtaining a conviction or providing an opportunity for defense.

Gosh. It just seems so much less totalitarian to fight piracy with books that are easy to access and download worldwide, and which are reasonably priced. Or, failing that, to fight piracy like every other crime: with the rule of law.

I have a set of pet peeves about the discussion of legalities in 19th century Britain.

One of those pet peeves looks like this: “A married woman was the property of her husband.” Or sometimes, even more explicitly, “a woman was her husband’s chattel.”

My problem with this is that it’s not true. No one educated in the Regency or Victorian period would have claimed that a woman was her husband’s property. And, in fact, if you read Mary Wollstonecraft’s “Vindication of the Rights of Women,” she does an admirable job of listing many of the problems with a woman’s place in the world, but she never once claims that women were a husband’s property.

The notion that women back then were like property is actually (a) either fairly modern; or (b) based on misapprehensions that were not mirrored in law, and were, in fact, punishable if acted upon.

For instance, there were some people back then who believed they could sell their wives. These people were wrong and ignorant; they could not. Some people today believe that the payment of income tax is voluntary. Those people are wrong, too. (In point of fact, if you go to that site, there’s a $300,000 challenge that they offer: identify the law that says you have to pay income taxes, and we’ll give you $300,000! I’m guessing that they somehow missed 26 U.S.C. § 1, and I would like my $300,000, thank you.) To give the wife-sellers’ views legal credence is like looking back on the U.S. 200 years from now and saying, “Gosh, it’s amazing that all those people voluntarily paid income tax.”

So let’s go to the first point: that the notion that a woman was property is a modern gloss on the actual situation. A wife was never considered a husband’s chattel. There are things you can do with chattels that you could never do to a wife. For instance, you can give chattels away. You can destroy them. You can sell them. On the other hand, if a man in Victorian England walks away from his wife, she has the right to go to an inn and order food…and he will be stuck with the bill. Even if he has not seen his wife for years, she can send bills for her necessary expenses to her husband, and if those expenses are necessary to her station in life, he will have to pay them. Likewise, it would have been illegal to dispose of his wife. She wasn’t alienable.

This is not to say that women’s place in society was equal to the man’s. The true relationship between husband and wife was actually closer to feudal lord and vassal. The husband was in charge of his wife, and was her legal face to the rest of the world. In some ways, this shielded the wife from many of her decisions; if she spent rashly, her husband would have to take the heat. In other ways, this left her with little recourse; she couldn’t sue her husband if he failed to pay her pin-money agreed upon (although she could sue his estate for the value of the money if he eventually died), and he had the right to control where she lived and to some extent, how. I wouldn’t have wanted to live in those times, and I’m thankful I did not.

But however inequitable the situation was, and it was awful, wives in Victorian England were not considered property–not by anyone except a handful of very ignorant, uneducated people. The notion that women were a husband’s property is actually quite modern–and it’s very much a function of our modern view of property as a set of rights.

There is not much to this post but this:

Trial by Desire made Publishers Weekly‘s list of Best Books. This kind of floors me–I can think of so many other books I would have chosen in my place–but I’m just thrilled to be there.

The other romance books on the list are Meljean Brook’s The Iron Duke (which I adored), Jo Bourne’s The Forbidden Rose (ditto), Eileen Dreyer’s Barely a Lady (haven’t read it, but will have to correct that), and Grace Burrowes’s The Heir (which I don’t think is out yet–but it’s definitely on my list).

I’m so, so honored to find myself on that list–particularly since it includes some of the books that I loved this year.

One last thing: a huge shout-out to my agent, Kristin Nelson. This is the third year running when she’s had an author (and the author of a mass-market title, no less!) land on the list of 100 best books: Sherry Thomas and Gail Carriger in 2008 and 2009. So go over and send her your congratulations on her three-year streak!

Someone sent me a link to a site that uncovers pirates by identifying information about pirates that they have posted on forums: IP addresses, home addresses, what they do for a living, and so forth.

I understand that piracy is a problem, but this site is not a solution.

First, this site has no safeguards in place to determine the truth of any charges. IP addresses can be masked or changed. Identifying information can be made up–or borrowed from someone else. Someone could be identified by name on that site when they haven’t done anything wrong, except to have a high school friend who thinks they are a nerd, who appropriated their name–and this could prevent that innocent person from getting a job, or from getting into college.

People pirate my books–but I don’t approve of defamation as a way to stop it.

Second, the behavior on the site borders on cyberstalking, and in some instances, crosses over the line. This is illegal in many states. The defense the author of the site provides is that first, the person she is cyberstalking has violated the law. This is not a defense. If someone assaults you in real life, you don’t get to cyberstalk them in return–you have to go to the police and file a report. If someone steals your computer in real life, you don’t get to shoot their dog. You go to the police and file a report.

Criminals have rights, too. They don’t lose the protection of the law simply because they have engaged in one criminal act. This is triply true when the person has never been convicted of a crime.

Second, she points out that the information is public–that is, she got it off public websites. This may be true, but you can stalk someone simply by standing on public sidewalks, too. The question is not “did you steal into their house and get something private” but “is this a form of harassment?”

This is vigilantism, plain and simple. And that’s illegal.

Third, the person running the site claims that she is not an author. If this claim is true, and to be frank, I doubt it, that means that she’s taking self-help measures in a case when it’s not even herself she’s helping.

I’m sorry, but copyright law gives a remedy to infringement to me, to the attorney general, and to those people who I have authorized to act on my behalf. My publisher and I have the authority to decide how we are going to deal with piracy of my work. That remedy, exclusive to me, is as much a part of the copyright statute as the right of distribution.

I haven’t authorized her–and I would never do so, particularly since her “method” of outing pirates is to include links to works they have pirated, even when the original link has expired, which seems to me to be a particularly odd way to contribute to the demise of piracy. For her to arrogate to herself the right to act in these cases without permission from the author is itself a form of theft.

I don’t particularly approve of piracy (although you’ll notice that I flinch less than many at the prospect). But I do believe in the rule of law. I believe in using the remedies given to you, and not enlarging upon them. And I believe that people who do things that are wrong are entitled to the protections that government affords us all.

This site is not a proper way to counteract copyright infringement.

This is a post about me:

First, look! (Or, rather, listen!) There’s a podcast with me talking about Trial by Desire. I started to listen to it, but then realized that I couldn’t stand the sound of my own voice. I don’t think I sound like that. Do I sound like that? But maybe you will like it! (I know, I know, a ringing endorsement.)

Second, I’ve been told that Proof by Seduction is an RT Reviewer’s Choice nominee for best first historical. Whee! How exciting is that? How exciting? If you are me, it is very exciting! Thank you, RT!

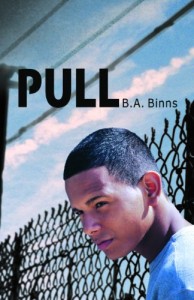

Third, and finally, something not about me: the winner of Pull by B.A. Binns is… BellaF! Bella, send me your snailmail contact, and I’ll get this book right out to you!

There’s a massive thread of painful death over at Dear Author about the geographic restriction problem.

Full disclosure: I sold Harlequin world rights, including translation rights, for my books, and they have done a phenomenal job of getting my book out there–and if you want to get an idea of how awesome take a look at this, which isn’t even a complete list–but even though I have been extraordinarily lucky in having a publisher that exercises the rights I’ve granted them, there are geographic delays involved and different pricing levels in different countries, and I’ve heard from readers that this is frustrating.

For those who don’t know, the geographic restriction problem is this: Historically, authors sold rights to territories. You would sell your U.S. publisher rights to publish your book in the United States, a U.K. publisher rights to publish in the U.K., and so forth.

In a world of print books, this just makes sense. It would make no sense to sell a US publisher both US and UK rights, because the US publisher would have no way to publish the book in the UK: no sales force to get the book into bookstores, no warehouse to store books when sent over to make sure they arrived on time, and so forth.

The end result, of course, is that some books would not be published in some territories. English-speakers who happened to live in Thailand would have to resort to expensive importing schemes. But the number of such sales lost would have been small, not sufficient to justify producing a book in the country of choice, and so publishers and authors shrugged–you can’t win every battle.

Enter e-books, and this stops making economic sense. In a world of e-books, you don’t want to slice things up by territory. You want to slice them up by language, so that the book is available in English, everywhere, at the same time, at the same price.

The problem is that we’re still locked in to the old system. Why did cowry shells work, in some parts of the world, as currency? Because people accepted them. And what would someone do if you tried to hand them some useless bits of paper in exchange? Well, they wouldn’t think much of it. And, in fact, if everyone else used cowry shells, you can’t walk in and say, “Hi, everyone, I’d like to buy your goats, and here are these AWESOME things called dollars.”

This is true even though paper currency is more efficient and easier to transport and less subject to being crushed when a goat steps on it.

Some of this problem is caused by authors. Authors want to maximize the amount of money we get, and so authors may only sell a publisher US rights. If the publisher sold the book to someone outside the US, they’d be in violation of their contract, and they don’t want to do that.

Some of this problem is caused by publishers. Some authors do sell publishers rights to world English–and the publisher won’t sell the book outside the US territory, because they know that (1) they can only effectively use the rights in the US (and by “effectively” I mean “both print and digital”); and (2) if they want to get the most money for what they’ve purchased, they want to resell those rights to a publisher in another territory; but (3) they will not be able to resell the rights to a territory if they do not give that other publisher exclusive rights in that territory. So a publisher with world English rights may choose not to release a book worldwide because it believes it will make more money if they try to get someone else to release it in another part of the world.

It’s even worse than I’ve made it out to be because the global consolidation of what used to be national publishers has locked publishers into the territorial divide by contract.

I could not insist in my next contract that Harlequin release the digital version of my book for a worldwide audience simultaneously. Or, at least, I could insist on it–but Harlequin almost certainly could not comply with my demand, even if they really, really wanted to.

I’m interpolating from available facts, but this is my basic idea of how Harlequin works. I sell world rights to everything to Harlequin S.A., a Swiss corporation. Harlequin S.A. then licenses my book to the various foreign arms of Harlequin, one of which is Harlequin Enterprises, Limited, a Canadian corporation–who produces the US edition. I am guessing that these foreign arms are in fact separate corporate entities, and that they are held together in the complex web of “Harlequin, Mills & Boon” by contracts that dictate territorial scope.

If Harlequin Enterprises, Limited, decided that it wanted to release e-books worldwide, it would probably be in violation of contracts it has with Mills and Boon over in the UK as well as Mills and Boon Australia. I’m guessing, but I suspect that there are very firm anti-poaching rules written into these agreements.

I suspect the same thing is true with the US and UK branches of Simon and Schuster, and HarperCollins and so on and so on.

At this point, if you sell your books to a major New York publisher, one that has foreign arms, they are probably bound to respect some foreign publisher’s territory by contract. And so even if you sell your publisher the right to release your book everywhere, simultaneously–they won’t exercise that right, and they probably cannot do so without breaking contracts already in place.

Like I said, this is interpolation: I have not, in fact, ever seen a contract between Mills and Boon and Harlequin Limited or HarperCollins Australia and HarperCollins US, but I can infer their existence on the basis of behavior.

In other words: Even if I wanted to sell something other than cowry shells, my publisher has probably entered into contracts that bind them to sell in units of cowry shells.

This is lock-in: a situation that may not be best for anyone today, but because of the way things arose historically, we’re stuck. At least for now. At some point in the future, when global e-books take off more than they have done now, the contracts between sister arms of publishers are going to start to disintegrate.

None of this problem is caused by readers, and they’re the ones who get stuck in the middle and slapped around and told they can’t buy books they want to buy.

This is definitely a failure. It encourages piracy. It leads to lost sales. It means that people who want to read books can’t. All of those things make me sad.

But I can’t fix this by making demands in my contract. My agent can’t fix this by making demands in my next contract.

I could fix this if I published with an epublisher that releases worldwide. I haven’t done that because I know that I will reach more readers if my books are in print.

And that is my decision–and I do take the responsibility and the blame for it, because it does leave some people out–but I know that I would get as much frustrated e-mail from readers who couldn’t find my book in Barnes and Noble and the grocery store as I would from readers in Thailand.

Brief Edit: Okay, we’re really up now!

Pull by B.A. Binns is one of the most powerful Y.A. books I’ve read all year.

David, the protagonist (you notice I don’t include his last name), is dealing with a lot for a kid in his senior year of high school. You see, a few months ago, his dad murdered his mother. His father’s in jail, and David himself, as the eldest in the family, has gotten the job of keeping his family together. Without the money he makes from an after school construction job, his sisters and he would have been split up around the globe, sent to distant relatives, many of whom don’t really seem to care about the family.

So David finds himself the man of his family, when he’s not even a man himself. And David does not know how to deal with what has happened to him. He changes his last name. In part, so that people at his new school (one that’s in a poor part of town, instead of the wealthier area where his parents used to live) don’t recognize either his skill at basketball or his father’s name. But in larger part, he doesn’t want to keep his father’s last name–just as he doesn’t want to visit his father in jail, doesn’t even call him “father” anymore.

But David’s suffering from post traumatic stress disorder as a result of the murder. And he’s struggling from a lot of things that feel absolutely real: He doesn’t want to go to college, doesn’t enjoy school, and does like girls–and as much as he likes them, he also blames them for the way they make him feel.

David is never a comfortable character, and he won’t make you feel comfortable (especially if you, like me, wince at the thought of someone not getting an education). And that, I think is what makes this book so raw and powerful. It is simply too easy to believe that David is real. To buy into what is a complex mix of teenage anger and angst and hope and self-hatred and arrogance all at once–and even though those things sound contradictory, when David lets you know how it is, in his short, terse, no-nonsense style, it’s real.

His character is so strong, so powerful, that even through (especially through) his terse denials, you can feel so much. I got more raw emotion from one of David’s curt “I don’t cares,” delivered at the right time than I do from most books.

And just to give you a taste of what he’s like, this from the first few pages of the book, after David has just had a traumatic flashback in the middle of gym class when the sound of the basketball hitting the court reminds him of a gunshot wound:

The gym teacher’s whistle sounds, the shriek knifing through my ears. He runs over from the sidelines where he’s been talking with another man while the inept group of students practiced passing the ball. His pale face holds wide, worried gray eyes. You’d think he’d never seen a guy downed by a basketball before. Probably hasn’t been teaching in the inner city very long. Probably still has ideals and intends to do some good or something.

Probably needs to get the hell out of my space.

And that’s David for you.

Like I said, this is not a comfortable book. But the day I got it, I was up until 1 AM reading, even though I had a 6 AM flight the next morning, and I got up half an hour early just so I could finish.

This book is seriously, utterly, powerfully compelling. And so I’m giving away a copy to one random commenter.