This is one of those legal-publishing posts that has almost nothing to do with my writing or romance, and everything to do with having law in my background. You have been warned.

One of the problems with law–as with medicine–is that it’s sometimes difficult to tell when your lawyer sucks. This is because people who hire lawyers often know very little about being a lawyer. So they accept what their lawyer does at face value. Even if their lawyer does, in fact, suck. Luckily, some lawyers believe in truth in advertising. They write legal briefs that suck on their face.

You, too, may be a sloppy lawyer! You, too, may want to make it easy for people to figure it out! If so, here’s how you can make sure that your clients and the entire world can tell how sloppy you are, in four easy steps.

1. Write a sloppy statement of jurisdiction.

Here’s an example of a sloppy statement of jurisdiction! This is sloppy in a lot of different ways. First, the person who wrote this brief didn’t bother to label numbered items as “personal jurisdiction” and “subject matter jurisdiction.” These two are not the same thing, and even though they both use the word jurisdiction, you should keep them separate. Is this sloppiness going to lose the case? Most of the time, no, but failing to comprehend the difference between the two can, in fact, occasionally lead to doom. For that reason, unsloppy lawyers usually take care to label these two different concepts distinctly. If you’re a sloppy lawyer, be sure to try not to treat these concepts separately.

Second, never take the time to say something like, “This court has federal question jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1331.” How hard is it to mention the actual statute granting the court the power to hear your case? Not hard at all! That’s why you skipped it.

None of this is going to lose this particular game (even though it could lose others), but it’s a great way to advertise your sloppiness. If you are not dotting i’s and crossing t’s here, you’re sending a sure signal to anyone reading your brief that somewhere, you failed to cross a t where it actually mattered.

2. Include extraneous, irrelevant detail in the fact section.

Here’s an example of an extraneous fact! A good fact section reads like a story. Every fact has purpose, and the person writing it knows precisely why they’ve included that fact. Each fact is the knife-blade of a scalpel, designed to cut through legal foggery.

But you? You don’t want to write a good fact section. You want to write a bad fact section. A bad fact section reads like an overbearing uncle who is trying to explain things that he doesn’t know too well. He throws in a ton of details just to prove that he knows stuff. Anyone who has a clue rolls their eyes when he opens his mouth.

(He gets stuff wrong. Nobody listens to him.)

Want to make sure your complaint sucks? Don’t ask yourself what facts are relevant and why. Write like an overbearing uncle.

3. Don’t bother proofreading.

Leave out words, just because they’re short and irrelevant!

Write awkwardly! Heck, if you can make someone read your sentence three times just to figure out what it means, you’ve made them read it three times! WIN.

Make sure that you are redundant, repetitive, and guilty of saying the same thing twice!

4. When making a claim under one section, refer to elements from another offense!

We all know how terribly inconvenient it is to have to prove every element of an offense in order to reach a finding of liability. I mean, seriously, how boring is that? Instead, if you’re not sure you can prove every element of an offense, substitute an element from a neighboring offense. Hey, maybe nobody will notice!

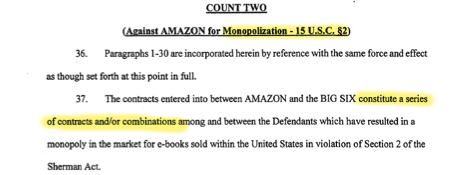

For instance, if you’re claiming that someone is guilty of monopolization, simply ignore the fact that a claim of monopolization under Section 2 of the Sherman Act requires you to prove that 1. someone has a monopoly, and 2. that it was obtained through unlawfully exclusionary conduct.

Instead, borrow an element from Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits contracts, combinations, and conspiracies in restraint of trade.

Here’s a great example of how to do this:

(Pro tip: It is legal to enter into contracts! Even when those contracts end up giving you a de facto monopoly!)

See? That promise that was made at the jurisdictional stage has been met. This is a lovely example of how someone being super-sloppy, and not checking the actual elements of the offense, could very well end up with this claim being dismissed unless the complaint is amended. Because you’ve confused some of the elements of a violation of Section 2 with the elements of a violation of Section 1, you’ve failed to allege one of the necessary elements–namely, that the defendants engaged in unlawfully exclusionary conduct.

I haven’t gotten into any of the other factual inaccuracies in this example brief. Since we have no merits briefs as yet, I haven’t even really commented on their legal theory, either. But whether there is some kind of colorable monopolization claim to be made against Amazon, I’d be surprised if this set of lawyers manages to do anything except be crushed like bugs when Amazon yawns and flexes its not-inconsiderable legal muscle.

Every time I hear the phrase “subject matter jurisdiction”, I think of Elle Woods.

Thank you for explaining this to all of us!

Crushed like bugs. I hope there’s a crunchy sound with that.

Ditto, Julie B.!

It is astounding that some of these legal errors are clearly intelligible even to those of us with zero legal experience (outside of watching “legal”-inspired movies, which probably counts as negative experience).

Thanks for the lesson