So far, the main argument I’ve heard in favor of the position that text-to-speech rights infringes on audio recordings and performances is that if you had a really good text-to-speech engine, people would no longer buy audio rights. Personally, I find that very sad–people who read books aloud are artists of immense caliber, capable of communicating nuance with very small variations in tone. I’d hate to think we value them so little that they could be so easily replaced. But even assuming that’s true, the fact that text-to-speech might cut into audio sales is not an argument that convinces me copyright infringement has taken place.

For those of you who care to follow me–which, based on my past copyright posts, is nobody–a brief explanation of why I think that is below the jump. WARNING: This post makes use of my execrable artistic skillz.

So here are the rights you get from copyright. In the US, these are defined by 17 USC s. 106.

I know, I know. You all bow before my phat drawing talent. What you see is a big block of rights, in typical Courtney oversimplified fashion. These correspond roughly to various sections of section 106. You have the right to make copies of your work. You have the right to make derivative works. You have the right to control distributions, and to allow (or not) public performances of your work.

I know, I know. You all bow before my phat drawing talent. What you see is a big block of rights, in typical Courtney oversimplified fashion. These correspond roughly to various sections of section 106. You have the right to make copies of your work. You have the right to make derivative works. You have the right to control distributions, and to allow (or not) public performances of your work.

Now, let’s take a look at something like — say — the distribution part. From the initial far away perspective, that mass of rights looks like one undifferentiated block. But when we get in closer, we see that it looks something like this:  It’s not just one right. It’s a whole slew of rights. And let me give those rights names that will make sense to authors. Over on the far right, that’s North American english rights. It’s followed by UK rights, Australian rights, New Zealand rights. It includes World English. (It also includes rights to distribute translations, for that matter, but if people are going to distribute translations in other languages, they’ll need to ALSO have the right to prepare a translation–so let’s not complicate matters by discussing those.) (Also, at this point you’ll recognize that the rights in question cannot fully be explained by 17 USC 106–since that is US copyright law–and you have to start going to treaties and foreign law to understand why your US copyright gives you the right to control distribution in New Zealand–but this is a distraction we don’t need right now.)

It’s not just one right. It’s a whole slew of rights. And let me give those rights names that will make sense to authors. Over on the far right, that’s North American english rights. It’s followed by UK rights, Australian rights, New Zealand rights. It includes World English. (It also includes rights to distribute translations, for that matter, but if people are going to distribute translations in other languages, they’ll need to ALSO have the right to prepare a translation–so let’s not complicate matters by discussing those.) (Also, at this point you’ll recognize that the rights in question cannot fully be explained by 17 USC 106–since that is US copyright law–and you have to start going to treaties and foreign law to understand why your US copyright gives you the right to control distribution in New Zealand–but this is a distraction we don’t need right now.)

Now, if we looked at North American rights, and we looked at how those looked up close and personal, we’d see that it too splits into a bundle of individual rights, just like we see distribution rights generally. It starts from the very beginning, and includes the right to distribute to Walmart, and goes all the way down to the chain at the very very end. Because you have the right to distribute your copyrighted work to the public by sale, it means that every time someone sells your book, they are effectively doing it with your permission. You are taking a teeny tiny little strand from a bundle and handing it off to the individual purchaser.

So what, exactly have you handed them?

It looks something like this. From far away, it looks like a single piece of string. Up close, you can see it’s another bundle of rights. This time, though, you can see that all the rights are tied together. You’ve given them a copy of your book. Implicit in that, you’ve also given them permission to get that copy of your book in their brain. In other words, you don’t just give them a copy of the book. You give them the right to read it. You give them the right to read with their eyes. You give them the right to read it aloud to their children. You give them the right to sleep with it under their pillow and dream about the world you’ve created. And you can’t take that away–if you give them the book, those other rights are indivisible from it. A book implies the right to read. It implies the right to imagine. It even implies the right to memorize and quote to your friends in extremely dorky fangirl fashion. So long as that “reading” is done in private, that reading can take a lot of forms.

It looks something like this. From far away, it looks like a single piece of string. Up close, you can see it’s another bundle of rights. This time, though, you can see that all the rights are tied together. You’ve given them a copy of your book. Implicit in that, you’ve also given them permission to get that copy of your book in their brain. In other words, you don’t just give them a copy of the book. You give them the right to read it. You give them the right to read with their eyes. You give them the right to read it aloud to their children. You give them the right to sleep with it under their pillow and dream about the world you’ve created. And you can’t take that away–if you give them the book, those other rights are indivisible from it. A book implies the right to read. It implies the right to imagine. It even implies the right to memorize and quote to your friends in extremely dorky fangirl fashion. So long as that “reading” is done in private, that reading can take a lot of forms.

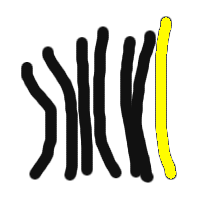

So here are some other rights that an author has. I mentioned them earlier–film rights, audio rights, translation rights, the rights to make screenplays, the right to make derivative works. Let’s focus on audio rights, the line in yellow. Audio rights are a complex beast, and I don’t want to get into what exactly is contained in them. But we know what audio rights basically are: The right to read a book aloud, record it, and distribute that recording.

So here are some other rights that an author has. I mentioned them earlier–film rights, audio rights, translation rights, the rights to make screenplays, the right to make derivative works. Let’s focus on audio rights, the line in yellow. Audio rights are a complex beast, and I don’t want to get into what exactly is contained in them. But we know what audio rights basically are: The right to read a book aloud, record it, and distribute that recording.

Now let’s take a look again at the rights that a user implicitly gets upon purchase of a physical copy, the rights I’ve been calling “the right to read.”

What the reader gets, along with a copy of the book, are many rights that are substitutes for various derivative works. That is, just as someone might use margarine or Crisco in place of butter in a recipe, a reader may use some of the rights that come along with the copy of the book in place of other rights the author has. For instance, if the reader has a great imagination, she can imagine a movie in her head, and thus decide not to see the movie based on the book. If she has a very large glass of water and a lot of time, she can read the book aloud to a friend or a nephew, and thus not purchase an audio recording. If she is an accomplished actress, she may even be able to produce a retelling of the book for her nephew that is superior to an audio recording–and ultimately, an author can’t do anything about that, because once the author sells her a book (or authorizes a book to be sold), he gives her the right to read in private, to imagine in private, to play games in private, in the world the author has created. It has always been the case that the reader may do things in private that cut into an author’s revenue stream. (In exchange for giving the reader those rights, I have to add that the author gets something substantial in return: The more of a book the reader puts into her brain, the bigger a fan she becomes. Soon, she turns into a rabid fan-zombie, who faces out all her favorite authors at Borders and shoves their books in the hands of unsuspecting readers. She buys every edition of the work in question. She even goes to see the movies, knowing they will never be as good as the book. Do not think this is all bad. These sticky little rights to imagine made Harry Potter an international phenomenon.)

What the reader gets, along with a copy of the book, are many rights that are substitutes for various derivative works. That is, just as someone might use margarine or Crisco in place of butter in a recipe, a reader may use some of the rights that come along with the copy of the book in place of other rights the author has. For instance, if the reader has a great imagination, she can imagine a movie in her head, and thus decide not to see the movie based on the book. If she has a very large glass of water and a lot of time, she can read the book aloud to a friend or a nephew, and thus not purchase an audio recording. If she is an accomplished actress, she may even be able to produce a retelling of the book for her nephew that is superior to an audio recording–and ultimately, an author can’t do anything about that, because once the author sells her a book (or authorizes a book to be sold), he gives her the right to read in private, to imagine in private, to play games in private, in the world the author has created. It has always been the case that the reader may do things in private that cut into an author’s revenue stream. (In exchange for giving the reader those rights, I have to add that the author gets something substantial in return: The more of a book the reader puts into her brain, the bigger a fan she becomes. Soon, she turns into a rabid fan-zombie, who faces out all her favorite authors at Borders and shoves their books in the hands of unsuspecting readers. She buys every edition of the work in question. She even goes to see the movies, knowing they will never be as good as the book. Do not think this is all bad. These sticky little rights to imagine made Harry Potter an international phenomenon.)

It does not matter how good a substitute the right to read is for audio rights or film rights. The reader still has those rights, and you can’t pluck them away from the copy of the book you sell.

What I would really, really like to see from someone who thinks that text-to-speech infringes audio rights is an explanation of how text-to-speech is not a part of the right to read. I want to see someone actually go through the statute and tell me what exclusive rights are violated when a user reads a book aloud. I want someone to identify the infringement. But just telling me that it’s an economic substitute for an item in an author’s revenue stream? That’s not enough. I’ve looked, and I haven’t seen a single legal argument being made for infringement. That doesn’t mean the claim is legally meritless. It just means that if there is any legal merit to the contention that text-to-speech infringes on copyright, I have been unable to find it on my own, and nobody has bothered to help me out.

Finally, as execrable an artist as myself.

Good post. I especially like the big glass of water and a lot of time part. I used to read aloud entire long chapters of the Dream of the Red Chamber to myself. Even chapters of the Bible, ones full of gems and descriptions on how to build nice things. Good to know I had every right to it. 🙂

Hey, I enjoyed your post…Copyrights Illustrated! Brings me back to the days of reading Marvel comic book versions of Robert Louis Stevenson. May all government documents be transformed into living color….

I know the following will be time consuming to read, sorry in advance for that. (And I have no finger-paints!) but I have some doubts over whether some of your arguments obtain. I guess the central thing is that there’s a whole area quite explicit to copyright that would be helpful to explore, which is the relationship of copyright to the public interest. Copyright essentially is the establishment (and I’m speaking informally here) of certain rights as reserved to the creator of an artistic work in contravention (sorry for the big word, I can’t think of the small one right now) of the public’s overall free use of ideas, language, etc. In other words, the rights protected under copyright are plucked from the cultural stream and isolated. Assuming the creator of the work doesn’t want to print out the manuscript and hide it under his/her mattress, he/she has a right to license and profit from licenses in various rights (sorry, I know you covered some of this above). But as these rights are set aside from public use, people (or unlicensed companies) cannot abrogate those rights in any way, and that stipulation is crucial. It is not so much the question of whether one can publically use someone else’s creative material, but whether one can profit from such use. I can read a work aloud to someone, sure (thank god for water!), but I cannot, seriously, read the work aloud in public if they’re paying to hear me do so. Now you might think that doesn’t bear on what you’ve discussed above, but keep with me. When a creator licenses some kind of right in their creative work, the licensor of that particular right now holds it as if they were the creator (subject to any limitations in the contract). In other words, the licensee substitutes for the copyright holder in terms of the rights enjoyed separate from the public’s use. So my two questions are: does the commercial bundling of talking-book technology along with a text of a work abrogate the licensee’s reserved right (reserved from the public) to solely enjoy profit from the rights they hold? And if I’m that licensee (a publisher)and I haven’t licensed the audio rights from the creator, only text rights, can I distribute my text product to an entity like Amazon to enjoy and sell to the public as a text/reading? It seems to me not. The second question, which is related, is are these talking book rights separate from audio rights or even possibly are they even a third kind of right separate from both text rights and audio rights? (Interesting to note that whether it’s one case or the other, book publishers in their contracts have always included talking book rights as a separate right granted, so setting aside their status under copyright, the publishing industry has always treated them separately.) To get back to the first question, I make the distinction like this: clearly you have the right to privately read your book to yourself, your neighbors, your cat, but not to people for cash money. And second, you have the right to buy a computer program that turns that text into speech, but you can’t then set that computer up on a stage (god forbid the sorry results of that) and have it talk to an audience whose sorry ass wallets have been lightened for the privilege. This also applies, crucuially, to putting it on the radio, where people alone in their own homes can listen to it, consituting the public. All this is germane, because Kindle is a device that is sold (at $349, I think) as a device that can read to you or anyone, or the public, whatever. There, it is Amazon that is giving you “a ticket” essentially, to hear the work spoken. If it is a feature that is inherent in the value of the device itself, and they are selling these works as downloadable on that device intrinsically, then it seems that talking book rights contributes to the value of the device. Whether they’re making a penny or a million exra for providing the feature, they’re profiting from rights they haven’t necessarily been grantedd to profit from, and they are charging the public for the privilege to hear. Setting aside that I think the idea that a talking book feature creates any sort of enjoyment whatsoever, while you yourself have the right to enjoy hearing creative works read on that Kindle in all it’s robotic stentorian tones, it’s probably the case that Amazon ain’t got the right to profit from selling to many peoples (the public) the device or “the work through the device” made more valuable/sellable because those people (whether separate or apart) can listen to the Kindle read it aloud.

Abstruse and recondite and I wish I had finger-paints…

Ha. Chris, I´m in Costa Rica & so my response is necessarily limited by my crappy internet access.

Here´s the problem with your argument. A Kindle, by itself, cannot infringe on copyright. The infringement, if it is one, doesn´t occur until the user instructs the device to read the text aloud. So really, what needs to happen (legally speaking) is that the user must infringe on copyright by using TTS, and the Kindle must vicariously or contributorily infringe by allowing that infringement.

The device itself cannot infringe.

So you can´t parse so finely. If the user has the right, Amazon has the right to allow the user to do so. Amazon´s right or infringement must be subsidiary to the users.

See? Keyboard sucks so much I cannot even spell my own name.