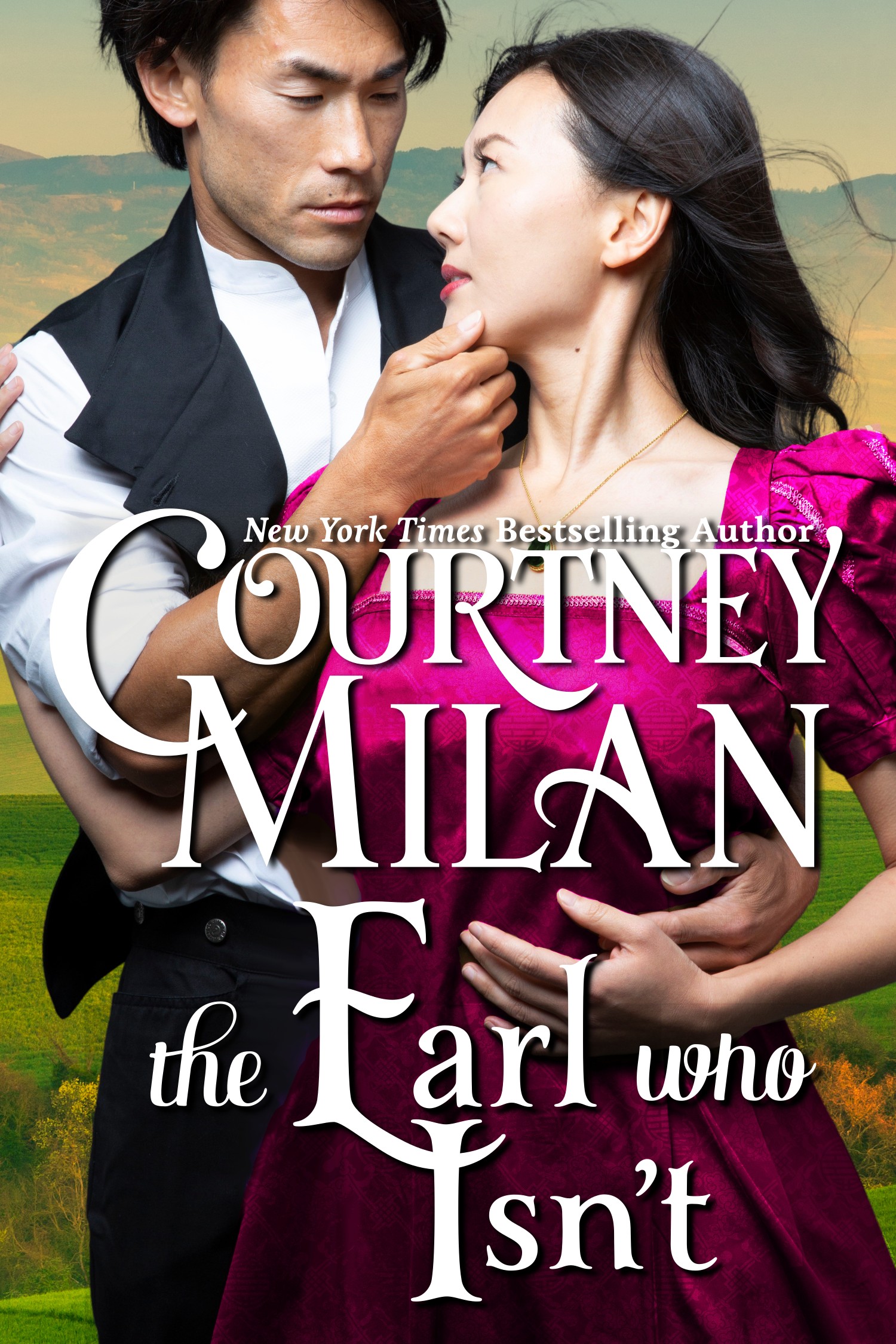

The Earl who Isn’t

Buy it

ebook: amazon | apple | b & n | google | koboprint: coming soon

audio: coming soon

Read More

about the book | excerpt | code name | content notesNobody knows that Andrew Uchida is the rightful heir of an earl. Not his friends, not his neighbors, not even the yard-long beans growing in his experimental garden. If the truth of his existence became public, the blue-blooded side of his family would stop at nothing to make him (and anyone connected with him) disappear. He shared one passionate night with the woman he loved…and allowed himself that only because she was leaving for Hong Kong the next morning.

Then Lily Bei returns, armed with a printing press, her irrepressible spirit, and a sheaf of inconvenient documents that prove the very thing Andrew wants concealed: that he is actually the legitimate, first born son of the Earl of Arsell.

What’s Andrew to do, when the woman he’s always desired promises him everything he’s never wanted? Andrew’s track record of saying no to Lily is nonexistent. The only way he can avert impending disaster is by stealing the evidence… while trying desperately not to fall in love (again) with the woman he shouldn’t let into his life.

The Wedgeford Trials Reading Order

1. The Duke Who Didn’t | 2. The Marquis who Mustn’t | 3. The Earl who Isn’t

Reviews

“Soon, we will have reviews of this book.”

—but not yet

Code Name

All of my books get code names. I have known that I will be writing this book, and what the vague outline of it was, since the first Wedgeford book, which you will know when (muffled noises) shows up on the screen and tells you what he was doing.

In any event, this isn't enough of a spoiler for me to embargo the code name: the code name for this book is "The Earl of Arse."

Excerpt

Wedgeford Down, Kent, England, 1893

Three of the yard-long bean seedlings had their first true leaves. They’d unfurled like green hearts overnight, and Andrew Uchida—if that was really his name—was delighted.

The long bean seeds had arrived as a single dried reddish-orange pod the length of Andrew’s forearm. He’d cracked the papery husk to find eight pale kidney-shaped seeds. Mathematics, skill, a little wild invention, and the magic of geometric progression had finally put Andrew’s goal within reach.

There were the deep clay pots he planted the seedlings in, designed not to disturb the sensitive roots of the young plants. Andrew had spent the entire winter poring over diagrams of magnets and wire coils, painstakingly constructing a water wheel turned by the irrigation canal that ran by his seed shed. In January, he’d turned on the first Edisonian incandescent light in Wedgeford. Those combined gave him a two-week start to the growing season.

He had kept his long beans a secret. Five of his eight seeds had germinated. He’d consulted calendars and done math: the fruit of these seedlings would go to seed themselves in twelve weeks, and he’d start the next wave of seedlings hopefully a hundred strong. By the time those went to seed in late August, he’d have enough for everyone in Wedgeford to sow a row of yard-long beans for a November harvest.

“Grow,” he murmured encouragingly to his little seedlings. “Grow and make everyone happy.”

The seed exchange that Andrew ran hadn’t been uniquely his idea. In some villages, seed exchanges were a way to share particularly well-performing varieties. But Wedgeford was not like other English villages. In Wedgeford, vegetables meant more than simple sustenance.

Andrew measured the first leaves with a ruler and made a notation in his journal. He’d told only his mother about his plan. It was early enough in the year that only the first early seed had been sown outdoors: radish and lettuce and carrots. The Wedgeford seed exchange was not yet bustling; the cabinet was still filled with plump paper packets of seeds, waiting for the weather to warm up. Journals lined the shelves above his workbench, detailing years of meticulous research on his part: notes on irrigation, drainage, soil amendment, which plants to train up a vine, and when to pinch sideshoots off cucumbers.

Morning light trickled through the large, south-facing windows at the other end of the shed, illuminating tables neatly lined with paper pots: tomato, cabbage, pak choy, peppers, aubergine, cucumber, melon. Most of those names would be familiar to English farmers, but the variety differed. The aubergine in Andrew’s collection would grow long, thin, and so dark a purple that they almost seemed black. The melons included the bitter variety, with its rough, spiked surface and winter melon dusted in white.

These were the vegetables that made Wedgeford unique, and they were grown from seed that Andrew had spent the last seven years of his life searching out, and all for one reason: for the elders who lived in this out-of-the-way corner of England.

About half of Wedgeford’s population was descended from various parts of Asia. They’d left their homes and families and settled here. Andrew had come to recognize the longing look in an elder might give to a garden, the heave of a nostalgic sigh.

That was the moment Andrew would hand over a vegetable that signified home. He lived for those moments: the morning he tossed over the first bitter melon to Mr. Peng, or the day he had silently brought dishes of brilliantly green steamed gailan, dressed in Wedgeford’s own brown sauce, out to a table at the inn.

There was the shout of joy. There was the noise and the clamor. Then, after all that had died down, there were people who found him and, through tears, said this: “Thank you. I feel like I’m at home.”

That feeling was heady: that someone might believe they belonged in a place. Experiencing it, even if only vicariously, was one of life’s greatest joys. What else could Andrew want?

The answer was simple. Andrew wanted yard-long beans.

Long beans: those were the legumes that the Mr. Beis and the the Mr. Pengs of Wedgeford imbued with almost mythic qualities. They sighed when the regular green beans (a mere four inches, bah) flowered in May, pale white and mildly sweet.

“So close to long beans,” Mrs. Li would lament.

In July, at the first harvest of beans, someone would always apologize that the beans were too watery in the stir-fry.

“Ei, what can you do?” Mr. Bei would say with a shrug. “They’re not long beans, after all.”

It had taken Andrew years to source the seeds, and he had no patience to wait longer. This year, no matter what else he accomplished—this year, at harvest, everyone would feast on long beans. And Wedgeford would feel like home to those who would never return to the country of their birth.

He paused in the act of reaching for the steel mister, a pang running through him.

Almost never to return.

Andrew was skilled at not thinking about the people (the person, in particular) who had left. She’d lived in Wedgeford since before she could walk; he hoped that wherever she was, she felt at home, the way he wished everyone did here.

Enough sentimental nonsense. The plants needed water.

But before he could act, the door to the shed opened. He froze, eyes darting momentarily to the incandescent light. It was light enough in here that it might not draw notice. It would be far more obvious to draw attention by unhooking it. Probably—

“Andrew!” The voice came from behind him. He paused, clenching his fingers around the cold steel handle. He recognized the voice, but it couldn’t be. It had been seven years since—

Footsteps sounded on the rough floor.

“Andrew!” the woman said, coming closer, interrupting his growing confusion and the rise of his heart rate. “Andrew, you’ll never guess what I’ve found.”

He turned. It couldn’t be, but it was.

The last time Andrew had seen Lily Bei they’d both been children. They hadn’t known it at the time—she’d been fifteen, and he’d thought himself so much older and wiser at sixteen. But the woman hurtling toward him was undoubtedly Lily Bei, all grown up.

Grown-up Lily Bei looked almost exactly like the young woman he’d known. She had not gained so much as a quarter inch of height, which was good, because he hadn’t either; he was still a finger-width taller. She still had freckles, visible even with ten feet between them, and a wide smile that nothing ever seemed to dim. Her eyes glowed with the endless enthusiasm that she’d always had. She was pelting towards him, recklessly running the way she had since she’d first learned to walk.

Andrew’s heart seemed to freeze in his chest. Maybe it had been frozen all these years, and it was just now coming to life with a great thump. He had no words, not even her name.

There were differences. She’d never used to bother with her hair, simply wrapping it up and stabbing it with a stick to keep the strands in place, which they almost never did. Now, her hair was in two complicated braided buns. She was wearing an actual gown, brown with gussets, instead of the dark Chinese trousers that she’d insisted upon when she was younger. Oddly, her run was a little lopsided because she had something under one arm, and it was hampering her movement.

It didn’t matter. She still looked like Lily, and he’d dreamed about her—wistfully, nostalgically, yearningly, the way a Wedgeford elder might think of a long bean—over the last seven years.

People had talked about her back then. Not a beauty, they’d said. Never going to get a husband, they said, not behaving the way she did.

Her face was flushed. Her eyes were wide and gleaming. Her mouth stretched in a smile, revealing the endearing little gap between her front teeth. She looked like his deepest, most selfish desire, one he’d hidden at the very bottom of his heart during the years of her absence.

Andrew set the mister back into place. He was going to need both hands to grasp hold of the whirlwind reality in which Lily Bei had come home.

She had always struck him as too exuberant to be confined with lesser social strictures like beautyor marriage. Lily, he’d always wanted to say to her detractors, was never going to get a husband. If he were lucky, a husband would get her.

Andrew Uchida—if that were really his name, and it wasn’t—had always known he could never be lucky in that particular way.

“Lily.” He tried to sound like a person who had not had his entire world flipped upside down by her arrival.

“You have to see this!” She darted up to him, bouncing on her toes, reaching for the satchel. “I have discovered the most amazing thing!”

“Lily.” Andrew felt as if he were moving at the speed of a shadow creeping in an arc behind a tree. She was the hummingbird darting between the leaves. “You are so far ahead of me. Slow down. I have not seen you in…” He pretended to calculate, as if he had not felt every hour of her absence as it passed by. “Seven years? You’re back?”

“Well, what else could I be? A phantasm sent to torture you?” Their eyes met, and he found himself unable to look away. He’d gladly be tortured, if it meant he could see her. She was the one who looked away. Her cheeks colored, as if perhaps she were thinking about what had happened the second-to-last time they had seen one another.

Well, she might not be remembering it; Lily never held onto things that meant nothing to her. Andrew remembered it.

They had, to put it plainly, had sex. Andrew had gone along with her plan, knowing that Lily was leaving. To her, intercourse was a means to an end. Andrew, by contrast, knew he would hold on to the memory for the rest of his life. He had known at the time that it was a mistake.

It had been the best mistake he’d ever made. He could feel the heat of his own blush, and he was just looking at the neckline of her gown, at the little constellation of freckles over her collarbone, disappearing into a no-nonsense stripe of black piping. He knew how far that trail of freckles went down the slight swell of her bosom. He’d had his hands on her nipples.

Lily was undoubtedly not thinking about that encounter at all.

Andrew pulled his eyes up from her breasts. “How are you?”

“Oh, bah.” She let out a puff of air, blowing stray strands of hair away from her eyes. “Pleasantries. How are you, et cetera et cetera. Can we get on with things?”

“I have been very well. It’s nice to see you again. I never thought I would.”

“Oh, nooo.” Lily let the syllable trail out. “The only thing worse than pleasantries is sentiment. Please tell me you haven’t turned into a maudlin gawp in my absence.”

Of course, Lily would never countenance sentiment from him. That wasn’t what they were. She’d said almost that exact thing when he’d started to haltingly say something about his feelings when they were in bed together.

So Andrew did what he always did when Lily was involved. He smiled, looked up, and ignored the pained, skipping beat of his heart.

“If by ‘gawp’ you mean…” He considered. “A groundbreaking, attractive, wonderful person—then yes.”

Lily pursed her lips. “Why would I mean that?”

“You see, the letters spell—”

“Never mind.” She waved a hand. “If you can posture about acronyms, we are done with pleasantries.”

Andrew shook his head. “Not so much as a handshake. After seven years!”

“Oh, for God’s sake. I know there is some key that unlocks actual conversation with real meaning instead of words exchanged for no particular reason. I thought we were friends enough to just skip all that blather, but since we aren’t, please tell me what I have to do to get to the point.”

Andrew considered this for a moment. “A handshake will do.”

“Very well.” She held out her gloved hand.

Andrew set the packet of long beans on the bench and took her hand in his. Her grasp was firm; the handshake was gentlemanlike. He could feel the pressure of each of her fingers against his palm. She was no nonsense, in sharp contrast to the well of nonsense that chattered in Andrew’s heart in confusion.

“I missed you, Lily.”

“Yes, yes,” Lily replied impatiently, taking the satchel out from under her arm. “Imagine I’ve said all the words that one says at this kind of time in response, instead of useful ones, such as ‘I have purchased a printing press.’”

“Have you?” He started. “Are you here to stay, then?”

“Argh.” She tapped two fingers to her forehead. “I wasn’t going to start with that. I’m just too excited. Here’s what I meant to say.” She undid the buckles on the satchel and reached inside. “You’re an earl.”

Andrew felt his head ring. She was rummaging around in the satchel as she spoke, not even looking at him as she delivered that sentence.

“What do you mean?” His voice sounded very high.

“I couldn’t possibly have said it more plainly. You are an earl. Or at least you will be, once the current Earl of Arsell passes away.”

Andrew considered himself a robust specimen of humanity. He was never sick. He never had spells. But right now?

He felt faint. Actually, physically faint. He had spent what felt like his entire life living in a way that left nobody in doubt as to his origins. There was no connection between him and the man who had technically spawned him. His father’s family had made sure of that, and his mother had been equally assiduous in pretending the marriage did not exist.

Wedgeford had been the perfect landing place for his mother: a place where distant travelers gathered. But Wedgeford was perfect in one other respect. By mutual agreement, the residents didn’t ask about each other’s past.

Everyone had left their country and loved ones; everyone had secrets. The magic of Wedgeford was that you were allowed to keep them.

It was beautiful, right up until the point when Lily Bei—impossible, unhindered Lily Bei—somehow managed to find yours out.

“I am very much not an earl.” His rebuttal sounded weak to his own ears. “Don’t say rubbish like that.”

“Bother. Am I going to have to give you the long version?”

Andrew felt as if he were watching himself through a set of birder’s stereo binoculars: as if he were both very large and very distant, all at the same time. He had to act normal.

Normal. What was normal?

“Lily, Lily, Lily.” He said her name thrice to cover the sluggish operation of his brain, because that was basically the only word circulating in his mind, paired with a simply unreasonable number of question marks.

How would he act, if he didn’t know? Ah, right. He’d laugh it off.

So he laughed. It sounded a little tinny. “You can’t just say ‘you’re an earl’ and expect me to say ‘that’s wonderful!’ and trot off to my earldom. You can’t tell me that you wouldn’t expect explanation. You always require explanation.”

“That’s fair.” Lily pulled a leather-bound book from her satchel. The cover was water-warped and the pages were slightly wrinkled. “Let me explain. I made friends with a retiring ship’s captain on my journey here,” she said. “I told him about my plans for a printing press, and he asked whether I thought he should publish his memoirs. He told me the strangest thing he ever experienced was—” She paused. “Well, technically, something else. This ranked only number four on his list.”

Four. The number of death. Of course.

“On board his ship,” Lily continued, “he performed a marriage between a man from Amsterdam and a woman from the Orient.”

“I see.” Andrew nodded solemnly. “That proves it.” This was awful. That sounded precisely like his parents’ marriage. There was nothing to do but immediately deny everything. “My mother is the only woman from the East, and everyone knows that Dutch men are all…who did you say it was? Some kind of earl? Do the Dutch even have earls?”

“I do so love being interrupted to tell me that the story I haven’t finished telling is incomplete.” Lily sniffed.

Andrew attempted to rein in his tearing panic.

“Continuing on: he told me that he’d thought it slightly strange at the time. He landed in Bristol because he was in need of dry dock repairs.”

Andrew kept the smile on his face. Worse and worse. His mother had landed in Bristol before taking another ship to Amsterdam. This was beginning to feel like that time when he was twelve and had tried to tell his mother that he hadn’t been anywhere near the claret that the inn kept for important guests.

It felt like he was being seen through.

“While he was awaiting repair, he saw a story about a man from Amsterdam inheriting an earldom—a son of a second or third son, or something. He matched the names—it was the man he’d married aboard the ship.”

A pit of awfulness yawned in Andrew’s stomach. “Are you sure?” Andrew asked.

“Of course I am!”

“Could his memory be off?”

“He saw it while he was on his way to turn his official ship’s log into the shipping master after the voyage. He checked it himself.”

Andrew felt the tight muscles of his worry relax slightly. “So the information about the marriage was in a log that is no longer in his possession?”

“He kept a personal log in addition to the official one.” Lily thumped the leather-bound volume. “Right here.”

Andrew swallowed in unease. “Did he.”

“Yes!” She opened it up, licked her finger, and thumbed a few pages. “Here.” She held it out to him. “That’s the marriage. Those characters there—that’s your mother, right?”

For a heartbeat, Andrew said nothing, then: “That’s not our family name. Our family name is Uchida.”

Lily gave him a blistering look. “It’s the name your mother has carved into the chest in her room. I’ve never asked questions—that’s not how we do things here, and why shouldn’t women get to change their names for any reason they’d like?—but of course I know.”

There had to be a response to that, and if Andrew’s wits were moving at anything like their normal pace, he would have given it. The problem was his thoughts weren’t moving at all.

“You see,” Lily continued triumphantly, “you’re the legitimate son of an actual earl. And—I asked upon arrival—he’s dying. Just think what you can do—what your inheritance must be. You could do anything you wanted, have anything you wanted.” She smiled up at him as if she were offering him a treat.

Andrew had never wanted much. The only thing he could think of in the moment was that if he were forced to be an earl, there would be no one to see to the long beans. Someone had to plant the long beans. It was supposed to be him.

“Do you remember that game we used to play?” Lily asked. “When Posh Jim first started coming to Wedgeford? When we talked about what we would do if we were dukes?”

Oh, no. Andrew had been a child then, and he’d panicked and played along. Now that memory gave Lily’s eyes a brightness.

“Think of the bills you could pass in Parliament,” she continued, because Lily in a tear of excitement couldn’t be stopped by anything except herself. “I know you enjoy agriculture; you’ll have so much more opportunity to make your mark. Andrew, you’re the best person I know, and to think that this is your fate? It’s marvelous.”

Andrew was not the best liar in the world. Really, he had only the one lie, and he’d never had to tell it because up until today, nobody had ever asked him if he was secretly an earl’s son. What the hell was one supposed to do in this circumstance?

Pretend, he supposed. Pretend that he was the person she thought, the non-earl turned suddenly earl. He had to pretend. He had to get away, and then he had to figure out how to fix this before anyone else found out.

“That’s….” What would someone who had not been failing to tell the truth to their best friend all their life say in this moment? They would probably…be happy? “Marvelous?” He bit his lip. “Unbelievable, of course—don’t ship’s captains logs have records of…giant nautiluses or the like?”

“That was months before. That day, it was just the wedding and the shark that spat up a crab.”

Andrew shook his head.

“How amusing.” He laughed again, perhaps a moment too slow, just to show that he was a normal person, and sharks vomiting out crustaceans were funny. He laughed the laugh of a man whose life had definitely not just been upended. It was, he thought, fairly convincing.

“In any event, I’ll believe it when you can make me an earl. But…”

Oh, no. He realized the error he had made as her chin lifted. Bloody hell. Had he just challengedLily to do it? Knowing what Lily did with challenges?

“But until then,” he said trying to tamp down his panic, “let’s keep it between us. You know how people tease.”

Lily frowned and looked at him. Her eyes, piercing and intense, seemed to see into his soul. “Of course I’ll have to tell your mother.”

“No!” She absolutely couldn’t, at least not until Andrew talked to her himself, and they could make sure they were telling the same story. “Don’t! It’s, ah, I mean…” He struggled for a reason. “Something we should bring up between just me and her. I’ll talk to her myself.” He very carefully didn’t promise Lily what he would say.

Andrew was not good at lying. He knew this from the claret incident. But—this was the one part of the situation that was slightly in his favor—Lily was worse at detecting lies than he was at telling them. It had taken her years to understand sarcasm. She was regularly taken in by falsehoods.

It had taken her two years to believe that Jeremy, the Duke of Lansing, who had come to Wedgeford for the annual village fair-slash-tournament, was actually the Duke of Lansing and just not telling them.

Lily couldn’t actually see into his soul. It just felt like it.

It had been seven years since last he’d seen Lily, and still he knew her every expression. This was the determined look of a woman who had seen a path before her, and had chosen to take it, no matter what the cost. Lily had made up her mind to do something. It was going to ruin Andrew’s life.

“Very well,” she said gravely. “You’ve stated your terms. You’ll tell your mother. Let’s get you your earldom.” She nodded at him.

What had he done? Andrew’s mind, already blank with terror, seemed to fill with a high-pitched noise. It sounded like the scream he wanted to emit.

“Great,” he said weakly. “Perfect. Wonderful.”

Another person might have asked about the lack of enthusiasm in his voice; Lily, however, was bad at telling when he was lying.

“Stupendous,” he added, because he needed more adjectives that described the exact opposite of how he felt.

He was going to have to undo this. Somehow.

But how?

“Not quite believable,” he heard himself saying. “I think I may be in shock. But of course this is all…delightful. Did I use that one already?”

“I don’t believe you did.” She smiled the sure, steady grin of a friend who had never known the depths that lurked in Andrew’s feral heart. “You deserve this. You’re the best person I know.”

If she really thought that, why would she do this to him?

Right—because she thought it would be wonderful to be an earl. What was he supposed to say to her? That he’d worked hard all his life to avoid exactly that?

Ha.

“Thank you,” Andrew responded with a wink. “I think the same of myself.”